The Battle of Eccles Hill

With the golden sunlight glimmering on their bayonets and the soft Vermont breezes tickling their green silk battle flag, the self-proclaimed Irish Republican Army marched off to war on the morning of May 25, 1870. Stopping on a country road outside a brick farmhouse just yards from his intended target, General John O’Neill ordered his troops into battle: “The eyes of your countrymen are upon you. Forward, MARCH!”

With O’Neill’s command echoing in their ears and the dreams of liberating their homeland dancing in their heart, 400 men in green uniforms charged into enemy territory—Canada.

Sparked by the adrenaline and Irish pride coursing through his body, 25-year-old John Rowe sprinted to the front of the pack as he passed the iron post marking the international border on the road between Franklin, Vermont, and Frelighsburg, Quebec. Atop the rocky cliff of Eccles Hill that overlooked the boundary, James Pell of Dunham, Quebec, crouched behind a time-scarred boulder and squinted down the thirty-inch barrel of his Ballard rifle. He remembered well how Irishmen had ransacked his house and smashed his piano on the Irish Republican Army’s previous visit to the Eastern Townships in 1866. As he held his rifle’s heavy hexagonal barrel and peered through its graduated sight, Pell focused on the first green figure rushing toward the bridge.

Pell’s finger squeezed the trigger, and the butt of his rifle bit into his shoulder. A sharp crack reverberated around the dale. Rowe collapsed to his knees, his hands still clutching his rifle. Pell’s shot pierced an artery on the Fenian’s left arm and tore through his lungs, leaving him to suffocate in his own blood on the bridge where he lay.

The Fenians were greeted with a further downpour of Canadian bullets after Pell’s opening salvo. The younger soldiers were struck with panic at the sight of their fallen comrade and their first taste of combat. They jumped off the bridge and crawled underneath it for cover. Others scattered, harboring themselves behind stone walls, outhouses, and chicken coops. William O’Brien of Moriah, New York, was shot dead. Others fell wounded while seeking shelter.

When a Canadian shot brushed the high felt hat off the head of the St. Albans Messenger correspondent Albert Clarke, who had commanded a company of the Thirteenth Vermont Infantry at Gettysburg, he beat a hasty retreat from the lumber pile on which he stood, under “no disposition,” he said, “to satisfy his curiosity further at the risk of his life.”

So many Fenians had taken flight that the rounds of ammunition rattling around inside the tin interiors of their swaying black leather shot pouches, according to one eyewitness, “could be distinctly heard even above the din of the civilians who were still scampering in both directions from the field.”

Although the Fenians outnumbered the Canadians nearly six to one, the forces atop Eccles Hill had the advantage of a nearly impregnable position. Thousands of years earlier, the retreating glaciers had sculpted the perfect fortress “behind which twenty men could have defied a thousand,” one newspaperman reported.

Frustrated, O’Neill gathered those troops within shouting distance in a protected area behind Richard’s house. He castigated his men in green for their timidity. “Men of Ireland, I am ashamed of you! You have acted disgracefully today; but you will have another chance of showing whether you are cravens or not. Comrades, we must not, we dare not go back with the stain of cowardice on us. Comrades, I will lead you again, and if you will not follow me, I will go with my officers and die in your front!” He then ascended a hillside orchard to rally his soldiers next to the Richard farm.

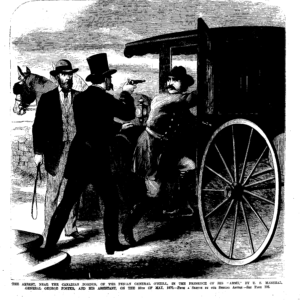

Returning, the general stopped to check on a wounded Fenian lying on the side of the road when a U.S. Marshal suddenly appeared at his side, threw him into the backseat of a waiting carriage, and declared him under arrest by no less an authority than President Ulysses S. Grant himself.

Given the arrest of their commander and the increasing desertion of soldiers, Fenian officers were left with no choice. They had to abandon their attack and hold their position until they could escape under the cover of darkness.

Once the Canadians began a counterattack, however, the demoralized Fenians fled into the woods back to their camp. In their haste to escape, they tossed their ammunition pouches and knapsacks to the side of the road in order to lighten their loads. One soldier whipped off his green jacket and turned it inside out because he felt betrayed by the Fenian leaders.

“It’s all up; and damn the men that got us up here,” the retreating soldier told a Burlington Free Press reporter. “I come from Massachusetts. They told us it’d be a glorious business, and a good job, and all that; and then got us into Canada and sent us down there to be shot at for two hours,” he said. “I’ve got enough of this Fenian business; and I’m going home.”

The Battle of Eccles Hill ended with two Irish-Americans dead and nine injured. For their part, the Canadians suffered not a single casualty. While newspapers joked that “I.R.A.” now stood for “I Ran Away,” O’Neill stewed in a jail cell. “I never was in a battle before that I was so utterly ashamed of,” he confided to a Rutland Herald reporter.

Anyone who thought that the utter humiliation of the Battle of Eccles Hill would dissuade O’Neill from ever attempting to attack Canada again, however, would eventually be proven wrong.

For more on the Battle of Eccles Hill and the five Irish-American attacks on Canada, order your copy of WHEN THE IRISH INVADED CANADA.